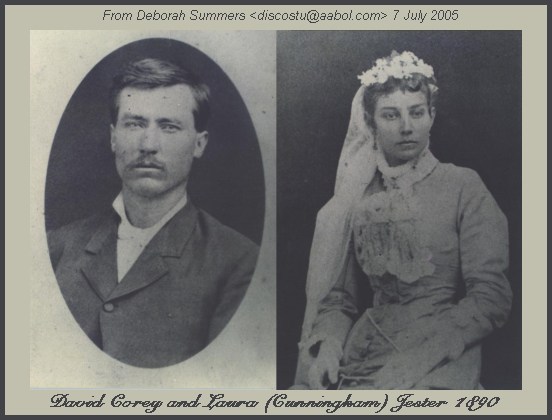

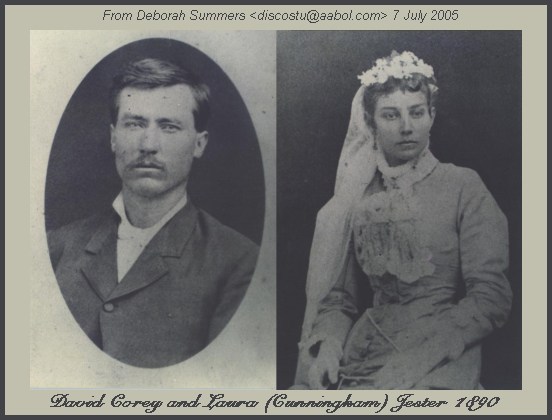

David Corey Jester

David Corey Jester, b. 1856, Elmwood, Mason County, Illinois, died 21 May 1952, buried at Jester, Greer County, Oklahoma.

David Corey Jester, b. 1856, Elmwood, Mason County, Illinois, died 21 May 1952, buried at Jester, Greer County, Oklahoma.

He married Katheryn Francis 16 May 1880 and together they had four children, Freddy Lee who married Allie P. Heatly,

Gertie Bell who died in infancy, Oda Pearl who married Oscar C. Frost, and William Francis who died in infancy

David married Laura Ellen Cunningham 23 May 1890 and had no children.

David Jester was a sick man when he got on a train in Mason county, Illinois, the autumn after Hayes was inaugurated president in 1877, and started toward the land of promise and hope at rails end just west of Dallas. It was the long road out he took, it turned out, because to save money he bought a scalpers ticket for $16, which ended at Palestine, in east Texas. The 21-year-old was suffering with malaria chills. Once he slept, tossing with fever, on a borrowed pallet in a frontier drug store.

Near Dallas he worked as a farm hand for $16 a month. He gathered corn for 20 cents a load, five loads a day, near Fort Worth he worked seven months for $13 a month and collected all at one time. Married in 1880 to Kate Francis of Grapevine, they had four children. Two of them died in infancy. A son Fred was killed in an accident as he worked on a flat tire near Mangum in 1929. A daughter, Mrs. Oda (Frost) Richards moved to Whittier, Calif. The first Mrs. Jester died in 1886.

With a little money in his jeans, and a horse, Jester turned from being a farm hand to a salesman for an itinerant photographer whose best business was making enlargements of old family tintypes. It was while riding around that Jester met Laura Cunningham, whom he married in 1890.

Lure of the land soon overcame the picture selling. Jester had a small farm at Valley View, Texas. There was little money. When one Jap Bray came back to Texas with title to a half-section of land in Greer county, and area then in hot ownership dispute between the territory and Texas, Bray was a bit discouraged. After some typical swapping talk, he traded the 320 acres to Jester for a mare and colt-and gave $25 cash to boot-which was the most appealing part of the bargain to Jester, he said recently.

The Jesters hooked up a light wagon and went to see their land in May of 1890, with no idea of what it would look like. They were pleased. Green grass spread over flat land and sloping prairie. Deer and Station creeks were half-full with clear water. With a borrowed plow Jester broke out seven acres (determined by pacing it out) and sowed wheat to establish evidence of ownership and use. Then they returned to Texas to trade a lot in town for three more horses, the bit of land for more stock.

In July they returned to Greer County to stay but their hopes were almost as brown as the seared grass that met their eyes. The creeks were dry, land parched; across the sod one could see dust rising from the wheels of outward-bound settlers. Jester traded a $140 horse for a plow, cook stove and a $100 horse for lumber and groceries, which he freighted from Quanah behind an eight-horse hitch. He built the one-room house that was to be a home, a store, town lot office, and general hub for the village of Jester. Then in October it rained.

The young pioneer broke out 20 acres of land then and sowed it to wheat. But the sod clumps were hard to walk over. Finally he cast the seed around, then plowed, then harrowed, simply for the ease of walking. A neighbor laughed at such methods but the crop averaged 20 bushel to the acre and was worth 66ΒΆ a bushel at Quanah, a long haul away across sandy Red river.

To fence the one-quarter section that held the improvements, Jester spent his spare time digging post holes with a crowbar, scooping the hard dirt out with a tin cup. He put the posts 36 feet apart, as far as he dared and still hold up a fence, but the distance around still measured two miles. Jester still could step land with such accuracy that he missed a quarter section only two feet from the distance chained by a surveyor.

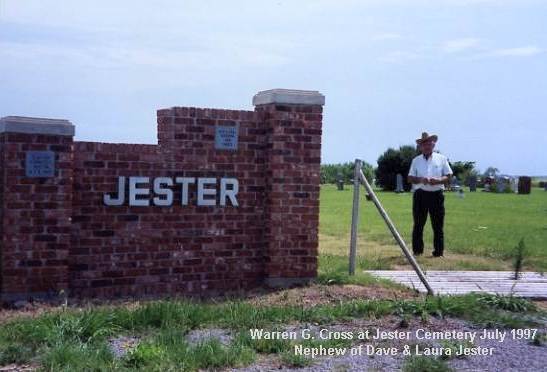

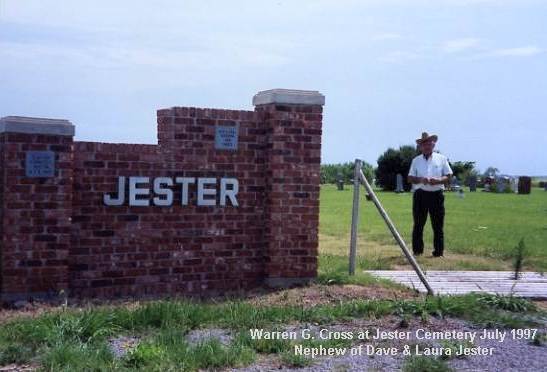

He was appointed first postmaster of the Jester post office, November 18, 1890.

When the Supreme Court awarded disputed Greer County to Oklahoma, meaning homesteaders could have but a quarter, instead of a half that Texas law would have given them, many pulled out. They sold land cheap and usually on terms. Jester bought all the land he could for cash, some more on the credit he had established in the community. He invested the land for his daughter and grandchildren, Clarence, Mildred, Frances, and Kate Frost.

As an early day freighter David Jester hauled lumber for the first bridge in Greer county, that over Deer creek south of Jester; he hauled the first Greer county wheat out to market at Quanah, Texas and the first wheat to Mangum's first elevator.

Since the days of lightning rod salesmen it was difficult to slip a phony deal over David Jester. Yet, he believed in taking care of his people, as he did during the depression when he put his tenants on a living allowance.

David Corey Jester, 96, founder of the Jester community, died May 21, 1952 at his home in Mangum after a three year illness. Funeral was Friday, May 23 in the Mangum Church of Christ with Rev. John Pigg of Madill, former minister, officiating and assisted by Riley Henry, minister. Burial in the Jester cemetery.

Sources: "Shade and Substance," Roy P. Stewart,

The Daily Oklahoman, Sunday, May 23, 1948, Section D-Three. Obituary,

Mangum Star News, May 22, 1952. http://genforum.genealogy.com/jester/messages/459.html