| Your

Guide To Oklahoma County Oklahoma Genealogy Part of the OKGenWeb Project | |||

| Updated: 03 Sep 2025 | |||

|

| |||

|

Former McIntosh County Sheriff Ervin A. Kelley was acting as

a special agent for the Oklahoma Bankers Association, which gave

him a new Thompson submachine gun, when he was shot and killed

by Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd on April 9, 1932.

Tulsa World When

he stepped out of the shadows into the headlights, Uncle Erv

deserved a better fate. Within seconds, two triggers fired 21shots. fter dawn, 10-year-old James Kelley learned of the gunfight. His mother had been summoned for an urgent call in the office of the Sand Springs Widows Colony, where they lived. She returned to their three-room "shotgun house" and gathered her five children around her. "She told us Uncle Erv had been killed," James Kelley said. There was grief but no surprise. They remembered Uncle Erv's haunting words from his visit two weeks earlier. "He wanted us to know he was on a special assignment to catch Pretty Boy Floyd and that something was about to happen and we may never see him again," he said. "He wanted to tell us goodbye, just in case." An uncle remembered James Kelley, now 85 and retired in Tulsa, talks without tears about those days. Sitting at his kitchen table, Kelley thumbs through a family scrapbook titled "A Good Officer, A Brave Man." It is filled with photocopies of dozens of news articles detailing his uncle's life, but the biggest headlines are reserved for his death. The ex-sheriff was the only Oklahoman killed by Charles "Pretty Boy" Floyd, many believe. No one disputes that his is the only murder to which Floyd publicly confessed. "Erv Kelley nearly got me," Oklahoma's most famous bandit told a reporter. "There was only one thing to do. It was either him or me, so I let him have it." It troubles James Kelley that his uncle has become little more than a footnote in the legend and myths of a criminal. Ballads, books and movies have immortalized Floyd and romanticized his life. His family -- mother, wife, son, brothers, sisters, nephews and nieces -- have been asked scores of times to recount tragic and fond memories of their famous kin. A recent interview, James Kelley said, was the first time he had been asked to talk about his uncle. He knows that Erv Kelley's five children, now deceased, were consulted only a few times. "Why is it that an outlaw can be so glorified?" James Kelley asked. "It gets to you. All the time a man tries to keep the world straight, he has been forgotten, and the guy who kills him gets all the recognition. "This isn't just about my uncle," the nephew said. "It's about all these police officers. They are overlooked all the time." James Kelley said he doesn't believe that Floyd was a benevolent Robin Hood-like figure, as he is often depicted, but he believes that scattering a few cents bought a lot of loyalty. "People were starving all over," James Kelley said. "I don't blame them (the destitute, for helping shield Floyd from law officers). It was only a few coins, but when you are starving, that was a lot of money." The shootout

Erv Kelley, 46, had led many successful manhunts, but the one for Pretty Boy Floyd promised the biggest payoff. The Oklahoma Bankers Association had announced a $1,000 reward for the capture of Floyd. Three other organizations offered $1,000 each, making the total bounty $4,000. The bankers declared Kelley a "special agent" and gave him a new Thompson submachine gun to complete his mission. Floyd, 28, was an ex-convict, suspected of five murders, including those of one lawman in Missouri and one in Ohio. By early 1932, his bank robberies and mayhem in his home state had made him Oklahoma's "Public Enemy No. 1." Kelley's ambush would take place three miles west of Bixby, a small community near the Arkansas River. Kelley recruited six veteran lawmen and two deputized farmers. They would be posted near the entrances to a farmhouse where Floyd was expected for a secret weekend rendezvous with his wife, Ruby, and 7-year-old son, Jackie. Several weeks earlier, Ruby had rejected Kelley's appeals to persuade her husband to surrender, and she had become the unwitting bait. Under a full moon, early on April 9, 1932, the vigil produced only hunger and chills. Kelley allowed most of the men to take a break from the stakeout. The two farmers remained at his side. Before 3 a.m., a car pulled up to the gate, its headlights suspiciously off. When the beams were abruptly turned on, they exposed Kelley, shouting his futile order to halt. Floyd fired his .45-caliber automatic handgun seven times, striking Kelley four times, twice in the chest. Kelley's submachine gun fired 14 times, most shots stirring up dust at his feet. He collapsed and died. Floyd was hit four times -- painful but not life-threatening slugs that all struck below his waist. He and crime partner George Birdwell sped away. Oklahoma's newspapers could not be printed quickly enough -- some printed extra editions -- to offer details about the dramatic showdown between the two local celebrities. Many were surprised that Kelley, whose instincts had always been right, had become the victim. Speculation was that he shouted a warning, giving Floyd a split second to react, for fear of hurting an innocent person. Some wondered why he had not worn his customary bulletproof vest. Most believed that his downfall was the farmers. When the shooting started, one farmer insisted that he didn't know how to use his automatic weapon; the other claimed that his gun jammed. Others say they cowered in the dark. "The mistake Uncle Erv made was having those two farmers backing him up," James Kelley said. Thousands of mourners

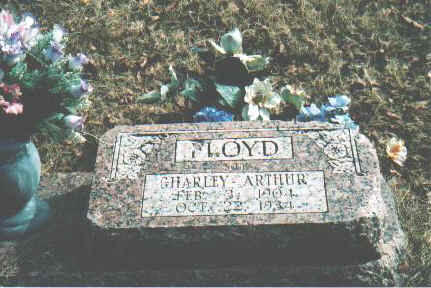

Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd was struck four times in the

shootout with Erv Kelley but survived until Oct. 22, 1934, when

he was killed by a posse in Ohio. James Kelley does not need a scrapbook to remember the sadness of April 11, 1932, when an estimated 3,000 people attended Erv Kelley's funeral. Newspapers reported that it was the largest in the first 25 years of Oklahoma statehood. From the front porch of Erv Kelley's two-story rent house, a Baptist preacher gave the eulogy. Inside the house, as the Kelley family peered from an adjacent room, mourners entered the front door, filed by the casket in the living room and exited through a back door. James Kelley recalled that many American Indians dropped coins in the casket as a display of friendship. "So many Indians liked him. He was fair with them," the nephew said. Kelley was buried in Greenlawn Cemetery in Checotah, next to his daughter, Lelia. In 1916, at the age of 2, she had choked to death on a peach pit. [NOTE: additional online search (4/2008) indicates he is buried in Akins Cemetery, Akins, Sequoyah County, Oklahoma, USA also see http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Lobby/3935/floydpics.htm & http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Lobby/3935/#Early%20Life & http://www.fortunecity.com/meltingpot/kuwait/55/id27.htm http://upress.kent.edu/books/King_J.htm

Aunt Dessie, the widow, received $50 from the Oklahoma Peace Officers' Association. She was buried next to her husband in 1959. Aftermath If Pretty Boy Floyd's criminal career seemed charmed before the Bixby shootout, it was cursed afterward. His wounds hobbled him for weeks, if not months, according to news reports. The reward for Floyd's capture increased to $7,000, and lawmen, National Guardsmen and bounty hunters swept through eastern Oklahoma looking for him. Famed aviator Wiley Post led an aerial search. In June 1932, Floyd dodged a barrage of bullets when a posse caught up with him near Stonewall, southeast of Ada. In November 1932, his most trusted partner, George Birdwell, was killed by a shotgun blast while attempting to rob a Boley bank. But with the killing of Kelley, the greatest damage seemed to be inflicted on Floyd's image in Oklahoma. For the first time, the headlines were not about a Sequoyah County boy who robbed "only monied men" and shared loot with the poor. This time, stories were about the death of a be loved Oklahoman, his grieving widow and children. Floyd may have been polite during his robberies and charming to hostages, but he showed that he would kill anyone who got in his way. It did not help his reputation when Ruby, in a front-porch interview with Tulsa World reporter Walter Biscup, appeared gleeful when she learned that Erv Kelley was dead. "Did you know Kelley trailed Pretty Boy for three months before he caught up with him this morning?" Ruby was asked. "Well, that son of a bitch won't trail him any longer, will he?" she said, laughing. She added that she wished other lawmen had been killed. R.D. Morgan of Haskell, an expert on Depression-era bandits and frequent author and speaker on the subject, said Kelley's sacrifice played a large role in disrupting Floyd's crime spree in Oklahoma. Historians generally agree that after the Kelley shootout, only one Oklahoma bank robbery should be credited to Floyd. That was in Sallisaw -- in his home county -- in November 1932. Floyd, who claimed to have robbed up to 60 banks, seemed to spend most of 1933 and 1934 out of state. Through family and intermediaries, he attempted to surrender four times if his life would be spared, but the FBI refused. "I think the shootout with Kelley, the close call at Stonewall and the death of Birdwell spooked him, and he got the heck out of Dodge," Morgan said. A date to remember

Oct. 22, 1934, was a coming-of-age day for James Kelley. It was his 13th birthday. He would go on to play second-string defensive end for the Sand Springs football team, to 46 years as an aviation electrician for the Navy -- in World War II and Korea -- and for American Airlines. He would go on to ask that cute Yankee transplant, Joan Clark, on their first date, to celebrate 55 years of marriage with her, to watch two sons and one daughter graduate from Oklahoma State University, his favorite school. "I've got to be careful. My granddaughter is going to OU," he said with a laugh. And on Oct. 22, 1934, James Kelley learned that Pretty Boy Floyd had been killed earlier that day by a posse in Ohio. The news did not bring him birthday cheer. "I was just glad he couldn't hurt anyone else," he said.

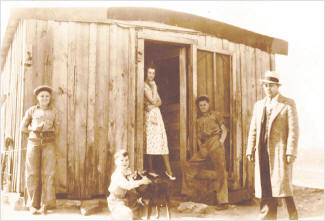

Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd’s wife, Ruby, stands in the

doorway of a farmhouse near Bixby the day after her husband

killed former Sheriff Ervin A. Kelley. Their son, Jackie, 7,

plays with his dog in the foreground. At right is Tulsa World

reporter Walter Biscup, who interviewed Ruby Floyd about the

shooting. The other two men are believed to be Ruby Floyd’s

brothers. Source: Tulsa World, Hollywood USA,

Resources: Most of the material for this page are from

existing old papers and microfilm on record at the Carnegie Public

Library of East Liverpool and from Records and Photographs in the

possession of the Dawson Funeral Home. Contributed by Marti Graham, April 2007. Information posted as courtesy to researchers. The contributor is not related to nor researching any of the above.

|

|

I hope you enjoy searching through our web site, as I've spent

considerable time on it. If you find other information on the web or elsewhere that might be appropriate for this page, please let me know. I'm am particularly interested journals or other records of movement into Oklahoma County, Oklahoma. | ||

| Site authored by Marti Graham, Coordinator Oklahoma County, Oklahoma part of the OKGenWeb Project |

Visitor: Home Page last updated: Wednesday, 03-Sep-2025 02:38:22 UTC This page updated: 03 Sep 2025 |

|

|

Copyright © 1997-2015. NO PART may be reproduced without author's permission. | ||

|

You found this information at //www.okgenweb.net/~okoklaho/misc/kelley_ervin.htm | ||