|

Henry Bellmon, 88, a farmer who became

Oklahoma's first Republican Governor, died on Tuesday

September 29. Bellmon also served 12 years in the US Senate

and one two year term in the state House of Representatives.

Bellmons body will lie in repose at the State Capitol from

10:00am - 4:00pm on Friday October 2.

Funeral services will be held at 10:00am Saturday at the

First Presbyterian Church, 1001 South Rankin in Edmond, and

at 3:00pm Saturday at the First Presbyterian Church

in Edmond.

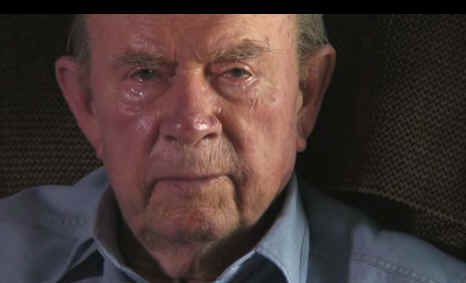

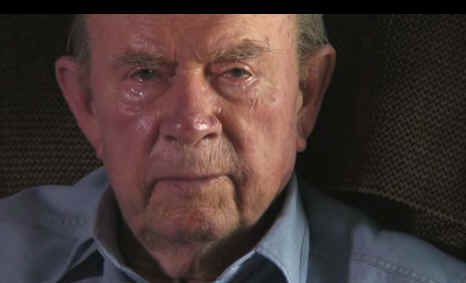

Former Oklahoma Gov. Henry Bellmon poses outside his family's

home near Billings.

BELLMON, Henry Louis, a

Republican Senator from Oklahoma; born on a farm near Tonkawa,

Kay County, Okla., September 3, 1921; educated in Noble County

public schools; graduated Oklahoma State University (then

Oklahoma A.&M. College) 1942; served in United States Marine

Corps 1942-1946; farmer and rancher; served in Oklahoma house of

representatives 1946-1948; State Republican chairman 1960;

elected Oklahoma’s first Republican Governor in 1962, served

1963-1967; while in office, chairman, Interstate Oil Compact

Commission, and member, executive committee, National Governors

Conference; elected as a Republican to the United States Senate

in 1968; reelected in 1974 and served from January 3, 1969, to

January 3, 1981; was not a candidate for reelection in 1980;

co-founder and co-chairman of the Committee for a Responsible

Federal Budget; appointed director of the Oklahoma Department of

Human Services 1983; elected Governor of Oklahoma 1986; is a

resident of Red Rock, Okla.

Military service: USMC (1942-46, WWII) awarded the

Silver Star

Governor of Oklahoma (12-Jan-1987 to 14-Jan-1991)

Father: George Bellmon

Mother: Edith Caskey

Wife: Shirley Osborn (m. 24-Jan-1947)

Love of the farm shapes Henry Bellmon's life

November 2007

BILLINGS — It was no secret that while Henry Bellmon was

governor of Oklahoma, he and first lady Shirley Bellmon went

back to the farm in Oklahoma as often as they could on weekends.

[Billings,

Noble County, Oklahoma]Even living in Washington as a U.S. senator couldn't keep

Bellmon away from the farm east of Billings. Bellmon, 86,

recently talked about his love of the land and

what it taught him.

"His desire when he was in the Senate was to go back to

Oklahoma every weekend and spend part of that time at the farm.

Most of the time that desire was realized,” said Andrew

Tevington, an assistant district attorney in Oklahoma County and

Bellmon's press secretary in Washington and chief of staff and

legal counsel while Bellmon was governor a second time.

Bellmon liked to be on the farm, getting his hands dirty and

doing all the things farmers do, Tevington said.

"We always knew when he had been on the farm and had

been working. It gave him time to think, and he would come back

with more ideas than we could handle,” Tevington said.

"This was home,” Bellmon said of the farm. "You

get your head cleared pretty quick.”

Bellmon's family

His father, George Bellmon, was a native of Kansas who had come

to No Man's Land with his parents and lived in a dugout beside

the Beaver River. Bellmon's father's first wife died on

Armistice Day at the end of World War I.

Bellmon's mother, who was the second wife of Bellmon's

father, George, taught school and looked after her parents until

they died.

Edith Caskey Bellmon was about 34, and Bellmon's father, was

about 10 years older when they met and married.

Henry Bellmon was the oldest of the four boys of his mother,

Edith, and his father, George. His father was a staunch

Republican who worked as a teamster, but he always kept land.

He was kind of a philosopher who had many sayings, Bellmon said.

One of the more important sayings was:

"You ain't learnin' nothing when you're talkin',” Bellmon said.

Bellmon took that philosophy into public life many years later.

"My mother managed to keep what I think of as a happy house,

a happy home for four boys who were pretty competitive. I think

she's probably the greatest woman I ever knew, with the

exception of my wives. She was determined that we get good

educations,” Bellmon said.

The last time he saw his mother was when he left to go into

the Marine Corps.

She worked as a school teacher during the war until she got

leukemia, and died while he was overseas.

Bellmon, a Marine tank commander, was part of a Marine group at

Tinian Island getting ready to go to Iwo Jima for what would

become a hellish battle. "They called me on the tank radio and

told me that my mother died,” Bellmon said

Back home

When the war ended, Bellmon was given leave and took the USS

Baltimore from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco.

Nobody was there to meet him, so he got a ride on a bus to a

nearby air base, took a train to San Diego and was put on an

airplane for Oklahoma City. "When I landed in Oklahoma City,

there was nobody there to meet me, so I hitchhiked home,” he

said. "I was a surprise to my dad.”

When he returned to the farm, he met Shirley Osborn. Their

families had been friends and the Osborns lived six miles from

the Bellmon farm. They married in January 1947. Bellmon says she

was the reason for his success in politics. She organized the

Bellmon Belles, a group of women who helped support him in his

campaign for governor, which he won in 1962, becoming the first

Republican elected governor. She was part of his campaigns for

the U.S. Senate and for a second term as governor. Shirley died

unexpectedly in 2000 while the family was on vacation in

Massachusetts. In 2002, Bellmon married Eloise Bollenbach.

Eloise and her late husband, Kingfisher rancher Irvin K.

Bollenbach, were longtime friends of the Bellmons.

Going Home: Henry Bellmon

BILLINGS — Trees cover much of the old red schoolhouse

that Henry Bellmon attended nearly 80 years ago, but nothing

covers his memory of it.

He walked a mile and a quarter to school, carrying a lard bucket

with a hearty lunch fixed by his mother.

“My first memory is the first day of school, eating fried

chicken and sitting on the (school’s) porch,” Bellmon recalled.

The one-room school had one teacher and 45 to 50 students in

grades one through eight.

Bellmon, whose mother pushed him to learn as fast as he could,

was advanced one grade.

“I learned almost by osmosis,” said Bellmon, explaining he could

easily hear what kids in higher grades were learning and

reciting.

The old school, now boarded up, sits at the corner of State

Highway 15 and the farm road that leads past Bellmon’s farm and

continues past the more than 100-year-old farm house where he

was reared.

Bellmon, who is 86, spends some days at the farm east of

Billings and other days at Kingfisher where his second wife,

Eloise, is from.

He sat in a chair in his den recently, discussing farm life and

whether things had changed much during his 86 years.

On an end table is a replica of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima

where Bellmon fought as a Marine and was awarded the Silver Star

for bravery.

Down a hallway are photos including ones of him and President

Nixon, and of his late wife, Shirley, with Patricia Nixon and

Judy Agnew, wife of vice president Spiro T. Agnew.

Another picture is of Bellmon in 1965 on the beach of Iwo Jima,

where he was a tank commander in 1945.

Wherever he’s been in his life — the governor’s office,

U.S. Senate or the Pacific island battlefields — Bellmon always

is drawn back to the land where he learned how to be

self-reliant and how to make ends meet through the Depression

and droughts of the 1930s.Schools

BILLINGS — Trees cover much of the old red schoolhouse that

Henry Bellmon

attended nearly 80 years ago, but nothing covers his memory of

it.

Billings and Marland

Billings and Marland were about the size they are now. His

parents didn’t go into Marland much. Billings was where they

attended church.s

“It had two grocery stores, two cafes, three filling

stations, a bank, which they still have, and several

churches,” he said of Billings.

His mother was superintendent of the Methodist Church’s

Sunday school for 25 years, he said.

But the family’s life revolved around the farm.

The farm life

The Bellmon

homestead is not far from his present farmhouse. His father

bought it probably 105 years ago, Bellmon

said. It had two rooms then but was expanded over the years.

Until Bellmon’s first year at Oklahoma A&M, now called Oklahoma

State University, it had no electricity

“Electricity was turned on before Thanksgiving” of his

freshman year in college, he said.

Asked what values he learned from farming, Bellmon said:

“There are some religious values — you put your

confidence in another year’s crop and wait a year before you

can harvest.”

Farmers get up early in the morning, and Bellmon

has displayed that trait throughout his life.

“I’ve seen him get out of bed at 4 (a.m.) and drive 20

miles and get on a bulldozer when the weather was inclement,”

said brother, George, said of the times after World War II when

they were in business together farming, building ponds and doing

other work with bulldozers.

Other times, George said he saw his brother, Henry, just lay

down at night and go to sleep near a job site rather than drive

all the way back home.

Farming wasn’t a battle with nature, as far as Bellmon

was concerned.

“I didn’t think of it as a battle as much as a

cooperative effort. We did what we could and Mother Nature did

the rest. We were never without food. Mother put up dozens and

dozens of jars of meats and peas and beans. We stored probably

20 bushels of potatoes in the cellar.”

At some point, someone had to go into the cellar and see if

any potatoes had spoiled.

“An experience you’d like to forget is picking up a

spoiled potato and squeezing it to find out if it was.”

His father saved a wagon load of wheat each year which was

turned into flour and used to make a product called cream of

wheat. It would last a year or until the next harvest, Bellmon

said.

One thing he didn’t enjoy was driving horses.

“I detested driving horses on ground that had gotten hard

and cloddy,” he said.

Bellmon

and his brothers helped work the farm, but there was fun too for

the four boys.

“Basically, we prowled up and down the creek, hunting for

squirrels and rabbits...we skinned possum and skunks and sold

their hides for 50 cents to a dollar each. We got spending money

that way. We didn’t participate in organized athletics because

there was no opportunity.”

Often, the boys from neighboring farms would get together in

somebody’s cow pasture and play baseball, his brother, George,

83, recalled.

Attraction of the farm

“In farming, you don’t move around much. You are tied to

the land, although I did make a living in Oklahoma City,”

Henry

Bellmon said.

It was no secret that while Bellmon was governor, he and first lady

Shirley Bellmon went back to the farm as often as they could

on weekends.

Even living in Washington as a

U.S.

senator couldn’t keep

Bellmon

away from the farm.

http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=B000351

http://www.nndb.com/people/276/000119916/

Complied and transcribed by Marti Graham, 2009.

|