Klondike School

District 49

Return to School Pictures Index

|

|

Klondike School |

|

This material is donated by people who want to communicate with and help others. Every effort is made to give credit and protect all copyrights. Presentation here does not extend any permissions to the public. This material can not be included in any compilation, publication, collection, or other reproduction for profit without permission. |

See Klondike Cemetery

Read Kathryn Thompson Presley's Stories of Klondike

Top Row: Unknown, Unknown, Heather ?, Mary Cockran,

Unknown, Lareta Gunter,

Unknown, Nevada Blankenship, Mr. Campbell - Teacher, Donna Furtrell, Jerry Richardson

Bottom Row: Twins - Billy & Eugene Reaves, Twins -

Harold & Darryl Driskill,

Twins - Paul & Silas Blankenship, Rebecca Blankenship, Marlyne Cockran,

Unknown, Peggy Gunter, Johnny Richardson, Unknown, Carolyn Thompson, Unknown,

Jean Furtrell - Teacher

|

|

Klondike School |

|

This material is donated by people who want to communicate with and help others. Every effort is made to give credit and protect all copyrights. Presentation here does not extend any permissions to the public. This material can not be included in any compilation, publication, collection, or other reproduction for profit without permission. |

County Superintendent of Schools Year Book

School – Klondike Garvin County District No. 49 School Year 1932 - 1933General Levy Fund 14.2 Mills

Bldg. Fund ___ Mills

Sinking Fund Levy 2.1 Mills

Total Levy 16.3 Mills

School Census

White 40 Male, 36 Female, 76 Total

Colored 00 Male, 00 Female, 00 Total

Aggregate 00 Male, 00 Female, 00 Total

Indians 0 Male, 0 Female, 0 Total

No. 8th Grade Graduates – 4

No. 12th Grade Graduates – blank

Model School 1290 Points

Accredited School – Yes

Revenue From Sources Other Than Taxes

County Apportionment - blank

State Appointment – blank

State Aid - 307.00

Federal Aid - blank

Transfer Fees – blank

Other Revenue – blank

Valuation of Assessed Property

Personal Property - 1745

Real Estate - 48782

Public Service - 30777

Total Valuation - 81304 (listed as all in dollars column but s/b 813.04?)

General Fund Appropriation – blank

Sinking Fund Appropriation – blank

School Expense this fiscal year – blank

Deficit at close of year – blank

Surplus at close of year – blank

School Officers

Name

Post

Office

Term Expires

Appointed Date

Director – J. A. Hatman

Pauls Valley, Rt. 4 March

1935 blank

Clerk – Ed Russell

Pauls Valley, Rt. 1

March 1934

blank

Member – T. T. Green

Pauls Valley, Rt. 1

March 1933

blank

Teachers

Name

Address

Yrs taught Monthly

Salary Certificate College/University Attended

Amos Ward

Pauls

Valley

5

$100.00

Life

blank

Florine Lasater

Pauls Valley

6

75.00 Life

blank

Length of Term Summer Term –

blank

Winter Term – 8 months

Opening School Summer Term – blank

Winter Term – October 17, 1932

Closing School Summer Term

– blank

Winter Term – May 26, 1933

Estimate Approved for school year

Gen Control $50.00

Teachers Salary 1029

Janitors Salary 10

Light Fuel Water 40

Repair of Furniture 50

Insurance 41

Int. on Warrants 60

Total $1280.13

Transfers

Name of pupil transferred to district From Dist No Cost of transfers

Wanda Baker

18

$75.00

Arvilla Osborn

18

75.00

Bertie Norman

18

75.00

Juanita Hatman

18

75.00

Acres in site – 1 1/2

Estimated Value of Bldg

$1000.00

Date Erected – blank, First Cost - $1600.00 Value of Equipment - $700.00,

Insurance - $1800.00

Total enrolled to date Total Days attended Av Daily Attendance

Days Taught

Total Boy, Grades

27

2561

16

Total Girl, Grades

28

2894

18

156

Total Boys, High School

Total Girls, High School

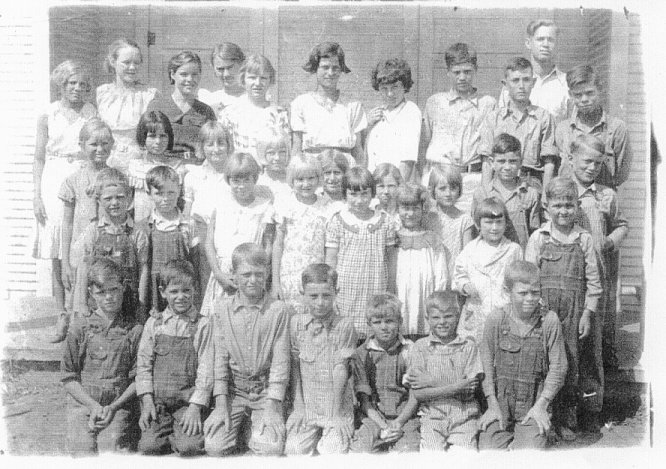

1935 or 1936

Top Row - second from left: Florene Lasater, Teacher & Amos Ward, Teacher

Second Row Down: Elsa ?, ? Osborn, Paula Gene

Blankenship, Beulah Brooks,

Blanche Gilbert, William Brooks, Paul Ross, Sherman Osborn

Third Row Down: Wanda Lee Blankenship, Unknown,

Mary Frances Hatman,

Unknown, Unknown, Rosetta Norman, Sarah Jane Hatman, C.L. Norman, S.D. Hatman

Fourth Row Down: Unknown, Unknown, Roxie Gilbert,

Betty Blankenship,

Louise Ross, Dorothy Driskill, Willie Gilbert, Wilton Driskill

Fifth Row Down: Unknown, Unknown, Kenneth Hatman,

Hubert Ross,

Unknown, ? Driskill, B.J. Russell, Unknown

If you know who any of the unknowns pictured here may be,

please let us know and we will add their names.

Submitted by Blake & Pat Blankenship

|

|

School House Stories |

|

This material is donated by people who want to communicate with and help others. Every effort is made to give credit and protect all copyrights. Presentation here does not extend any permissions to the public. This material can not be included in any compilation, publication, collection, or other reproduction for profit without permission. |

By Karthryn Thompson Presley

Charles Darwin Comes to Wild Horse Creek

(this is a true story from Klondike though I changed the names)

If you drive west from Choctaw Springs, out toward Elmore City, you will come, eventually, to Wild Horse Creek. It meanders lazily through a broad valley, rimmed with prairie to the east and rugged hills westward. It's not the prettiest part of Little Dixie, my corner of Southern Oklahoma, but there is a "certain slant of light," and, as grandpa always said, " these are the hills of home." I remember them as gentle, green hills, though they were more often stark and brown. I can shut my eyes and smell the pungent jimson weeds and sunflowers, hear cicadas in postoak trees, a whippoorwill at twilight, and a lone coyote in the night.

All my folks lived on little patches of red earth up and down the valley of the Wild Horse. They had drifted into Indian Territory from Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee after the Civil War, which we called the War Between the States. They had only just begun to recuperate from war's desolation when the Depression and Dust Bowl came with great "black blizzards" sweeping down from Colorado. we watched our topsoil blow away, eastward across the tortuous way my folks had come, all the way to the Atlantic.

None of us out at Wild Horse Creek had ever heard of Charles Darwin or his Theory of Evolution until the year Mr. Adam Barnett moved into the teacherage. We had been hit hard by the Okie Exodus to California and since our enrollment was down that year Mr. Adam was the entire staff of the school; principal, teacher of both the "little room" (grades 1 through 4) and the "big room" (grades 5 through 8). He was also the janitor and general handy man. He had a degree from the University of Oklahoma, and folks said he was the smartest teacher we'd ever seen out at Wild Horse.

We never knew by what convoluted paths he had arrived at our community. Certainly it was not a choice assignment; the pay was poor, and both school and teacherage showed signs of advancing age. There were cracks in the walls that let in winter winds and summer heat. Water had to be carried in from the school house pump, and the ancient privy behind the teacherage was shrouded in cobwebs and shuddered in the moaning wind.

In his deep, melodious voice, Mr. Adam Barnett could quote great chunks from Shakespeare and from the Bible. He knew more American history than any other teacher I have ever known and kept us all spellbound with stories about the early days of America, the War Between the States, and the Great American West. But science was his forte, and he made us love it, too, until he sprang Evolution on us. We were mutually astonished, Adam Barnett, my classmates, and I. We had never heard of such a thing, and he could not believe we had never heard of it.

As Defender of the Faith, I felt obligated to explain to our teacher that he was a heretic, but I was struck dumb. We all were. We just sat there with the October sun slanting in the west windows and glared at our peerless pedagogue until he rang the hand bell for recess with obvious relief.

Willie Mae McDougald took it hardest. A small, frail child (the smallest in the fourth grade), Willie was never quite clean. With the forthright cruelty of children, we called her "Wet Willie." She had a weak bladder which betrayed her in moments of stress, and the Darwinian conflict was stressful. I was both embarrassed and annoyed by the yellow, malodorous puddle that regularly filled the aisle between us. Willie's small face turned crimson and tears oozed from her tightly squeezed eyes. "I know it ain't so," she told me later; "I know Pap would have told me if we was kin to any monkeys."

The stress of evolution had far ranging repercussions: it followed us to the playground where we usually played "Annie Over" or tag or mumblety-peg during recess. That day we huddled in little groups and discussed Evolution.

In his confusion, Junior Campbell made a trip to the privy and forgot to zip his pants. Later, when he was "showing off," walking hand over hand across the high bar that held our swings, the other boys began to point and giggle. Looking up, I watched in horror, transfixed, mesmerized by that small pink appendage, dangling above me like an embryonic mouse. At that moment, my lifelong romance with Junior began to go sour; still, it might have survived, I might have been compassionate if he'd had the sense to be embarrassed. But no, Junior swung to the ground, zipped his pants with a flourish, and took a bow, in one graceful movement. How mysterious, how mercurial is the heart of a woman; my love for him turned to contempt in an instant, even as Michal's love for King David had done.

I turned my back on Junior and joined the group of older students plotting revenge on Mr. Adam, the heretic. Back then, evolution was the craziest thing we had ever heard; God had created the Heavens and the earth; He had made man in His image; everyone at Wild Horse knew that. In our isolated valley, we had totally missed out on the Scopes trial. For Adam Barnett to promote evolution seriously damaged his credibility with us, so we planned to teach our teacher a lesson.

While Mr. Adam visited the privy, Luther and Pete Blevins sneaked inside the schoolhouse and put a thumbtack in the teacher's chair, then hurried out to the pump to fill the trash can with cold well water. Back inside, they spread crumpled paper wads over the water.

The fun began right after recess. Mr. Adam always tamped the waste basket with his foot at least once in the afternoon, and that day he got an icy foot washing. His face reddened only slightly, and when he sat on the tack, he managed to react hardly at all. He was a cool one. He was thoughtful as he listened to the primary reading groups recite and was very quiet as he dismissed us for the day.

Next morning, Mr. Adam was still subdued as we recited the Pledge of Allegiance and had our morning prayers. Then, he read a poem about some blind men and an elephant and prodded us to unlock its meaning; that different people have different views of any subject, and there are so many facets to the truth it is foolish to condemn a viewpoint other than your own. We got his message all right, and we listened silently while he declared the value of open minds. Later, when he talked to us again about Charles Darwin, we still sat in stony silence. When Adam tried to ring the bell for morning recess, it was mute. Someone had stuffed it with paper wads. Adam's face reddened again, but he didn't say a word as he plucked out the paper. After recess, he talked at length about loving your neighbor as yourself. He told us he loved and respected the Bible as great literature, but he had been an agnostic since his first year at the university. He had to explain agnosticism to us, as we weren't familiar with that word either.

The Holy War raged on at our little school for weeks with the student body on one side and Mr. Adam Barnett and Charles Darwin on the other. I'm not sure why we never tattled to our folks; perhaps it was some primitive code of honor, but finally, I did ask Papa and Grandpa if they had every heard of Charles Darwin and Evolution. Grandpa thought they might be a traveling medicine show or an act on the Chautauqua circuit, but Papa remembered reading something about Darwin in the Kansas City Star, and he quizzed me until I told him why I needed to know. For some little time, he rubbed his chin like he always did when he was worried. As a parent and as president of our school board, he was concerned about what went on at school, but he was also one of the fairest, kindest men who ever lived, and he liked to take his time before making important decisions. I'm sure he hadn't heard about academic freedom, but he knew the power of ideas. I think he also believed the things he'd taught me by precept and example were powerful enough to withstand any onslaughts by Adam Barnett and Charles Darwin.

I don't know how long our war would have gone on or what the outcome might have been had it not been for Mr. Adam's trouble in the toilet. We heard him yelling late one afternoon and Papa went out to find that Adam had been bitten in his "nether regions" by a black widow spider lurking in the privy. Papa comforted him as best he could. Later, he and grandpa drove the trembling schoolmaster in to town to see a doctor, who kept Mr. Adam overnight, mostly to calm him down. Papa and grandpa sat with him awhile and had prayer with him before they left.

Mr. Adam resigned at the end of that year, joining the swelling tide to California. Years later, we heard he had gone to Golden Gate Seminary and entered the ministry. While we were never able to verify that, I like to think it might be true.

In more than the half century since, I've never encountered Darwin's Theory of Evolution without remembering Mr. Adam Barnett, Wet Willie, and Junior Campbell. And I know my father, to the day of his death, remembered Mr. Adam. He always smiled when telling me about that wild night ride into town: "I tell you, Kathryn Jane, that Mr. Darwin don't provide a lot of strength for living and not one bit of comfort for dying."

First Published in CCTE Journal

Schoolhouse Memories

If you drive the back roads of rural America today, you will come upon abandoned one or two room schoolhouses, standing vacant and forlorn, with weeds growing where children once played. Such modest schools formed the backbone of American education for 250 years. Seldom has so much been accomplished with so little. Certainly country-school education had occasional problems; poorly trained teachers; poorly equipped schoolrooms; lack of books; insufficient time, as teachers hurried from class to class; and lack of compulsory education laws, resulting in poor attendance as farm youngsters stayed home to help with chores. Moreover, the isolation and loneliness of rural schools could be oppressive.

Nonetheless, those of us who treasure memories of such school days know there were compensations for the harshness of our lives. We remember picnics, pie suppers, and cake walks, where first love blossomed in he security of a small world, and where our schoolmates were an extended family. We remember teachers who changed our lives - teachers like Miss Florine Lasater.

When I first read Wilder's Our Town, my high-school English teacher asked the class to select a day of our lives to live over again, as the character Emily did. Without hesitation, I chose the day that snow kept everyone away from Red Branch School except Miss Florine Lasater and me. She could have sent me home and enjoyed her holiday. Instead she closed the schoolhouse, and we retired to her one-room "teacherage" behind the coal house. She built a roaring fire in the wood stove, and we popped corn, made a pot full of gooey fudge, and played Monopoly for hours. We ate our respective sack lunches in companionable silence and afterward built a snowman in the school yard. We wrapped a red woolen muffler around his neck and topped him with one of Miss Florine's ridiculous flower-bedecked straw hats.

The following Monday the other 27 students returned to Red Branch School, but I never forgot that glorious day I'd had Miss Florine all to myself.

As absolute sovereign of the "little room," grades one through four, she was my teacher for three years. Mr. Amos Ward taught the "big room," grades five through eight. Students who ventured beyond the eighth grade - and most of us did - caught a school bus at sunrise and rode eight miles into town.

Miss Florine presided like any reigning monarch in the "little room." We knew little of democracy, and we soon learned that it was far easier to memorize our "times tables" than to explain to the teacher why we had not. We mastered the Primary Reader in record time for the joy of seeing our teacher's smile.

Miss Florine always had our room warm and welcoming on winter mornings and rang the hand bell with great vigor as we streamed up the red clay road. First graders sat next to the great black monster that was our coal stove. The older you got, the farther away you sat, with fourth graders shivering against the wall. Miss Florine listened to us recite, one row at a time, giving each child individualized assignments to work on while she listened to the other rows. Absolutely no time or motion was wasted, and few disciplinary problems arose.

We worked intently until about 10:00, when Miss Florine said, "All right, children, let's play awhile." Then we all streamed outdoors to the water pump and to the "his and her" privies standing sedately at a respectful distance from either end of the school building. With seventh and eighth grade boys manning the water pump, the rest of us lined up at the spigots to drink our fill. Then we had just enough time for the game of the day. With no discernable signals, we moved in unison through the school year from kites to mumblety-peg to jacks to yo-yos to Red Rover to softball to tag. On inclement days, we played blackboard games; tic-tac-toe, hangman's noose, connect-the-dots, and other games.

When Miss Florine's hand bell summoned us back to work, we were diligent for another hour and a half, and then our came the syrup pails, filled with cold biscuits, sausages, boiled eggs, and sometimes pimento cheese sandwiches.

All of us pitched in to help Miss Florine and Mr. Amos with their janitorial duties. Older boys kept the coal buckets full, and on Friday afternoons, we washed the chalkboards and dusted erasers out on the cellar door. However, before that, Friday afternoons were given over to spelling bees and ciphering matches. Mr. Amos opened the partitions between big and little rooms, and the entire school squared off in competition. Nancy Spencer and I were usually the best two spellers.

During the seventh grade, my family moved to Galveston, Texas, and I found myself in a large, overcrowded junior high. Although Mama and Papa worried that I would be behind my city classmates, they soon learned that Miss Florine and Mr. Amos had done their jobs well.

Later, after I became a teacher, rural schools came under criticism; they did not offer enough curriculum choices, and rural students were disadvantaged - disadvantaged? Us? Those educational bureaucrats never knew Miss Florine and Mr. Amos, who simply never tolerated failure or disadvantage of any kind.

First Published in Mature Living

Glady Would I Learn - and Gladly Teach

Sylvia Barret, the frustrated young teacher in Up the Down Staircase, confessed she became a teacher so she could "make a lasting impression on the heart of a child." Probably most teachers would admit to the same ambition. We secretly hope that, at their 30 year reunions, our students will reminisce about the dear old English teacher who taught them all they know. Unfortunately, it seems increasingly difficult to make any kind of impression on the hearts of modern children - lasting or fleeting.

Exactly what kind of teaching is it that permanently influences lives? I am haunted by President Garfield's often repeated description of a good education; "... a log with Mark Hopkins at one end and James Garfield at the other." Who was this Mark Hopkins and what did he have that I have not? Perhaps it was only a quiet place and a student eager to learn. These are rare on campuses of the 90s.

Did Mark Hopkins ever try to teach Shakespeare in the midst of a riot? Did he ever expound the fine distinction between who and whom to 20 ninth graders in various degrees of hallucinogenic trance? Did he ever give a spelling test, calmly, while the building was searched for bombs? Did he ever have breakfast duty and watch 300 teenagers run amok because the toast was too brown? Did he ever skid through smashed dishes, scrambled eggs, and orange juice trying to restore law and order? I've done all that and more and, while I may not have made a permanent impression on the heart of any child, some of them have made lasting impressions on me!

Long ago, some of my own teachers made lasting impressions on me, too, teachers like Florine Lasater and Amos Ward. They taught in a two room country school during the Depression, right in the middle of the Dust Bowl. Miss Florine taught the "little room," grades one through four, while Mr. Amos taught the "big room," grades five through eight. We had no multi-media materials, few and precious books, and those of us who were affluent had two school outfits - one for winter and one for summer. Some of us wore shoes in the winter.

None of that mattered much, because Miss Florine and Mr. Amos made living and learning exciting adventures. I can remember no dull moments in their classroom. In the spring we collected wild flowers, insects, and snakes from the hills behind the school house. Once, when we were studying our Indian heritage, Miss Florine crawled around with us in creek beds until we found a vein of clay. We dragged washtubs fill of the red muck back to school and set up our own Indian pottery operation.

One year, I was the only child in fourth grade. With Miss Florine's help, I worked up an exhibit following a lowly cotton seed all the way through planting, cultivation, harvesting, manufacturing, and marketing. All my fourth-grade lessons - math, history, English, and science - revolved around cotton. That fall, when school closed for us to pick cotton, I knew we were an important part of a great industry. Even so, I could hardly wait to return to school in November.

Years later, when studying Our Town, I was asked to choose, like Emily, a day of my life to live all over again. It was simple. I chose the day heavy snows kept everyone away from school except Miss Florine and me. She could have sent me home; instead, we popped corn and made fudge on the wood stove and played Monopoly until evening shadows fell.

It was when Miss Florine asked me to tutor first graders in the cloakroom that I got my first taste of teaching. After that, there was never any question about what I would do with my life. Marriage and rearing a family merely delayed me a few years; then I returned to the local university to complete work on my degree. The day before graduation, the head of our Education Department summoned me into his office. Pinioning me with beady, gray eyes, he intoned, "I would be remiss in my duty, Mrs. Presley, if I didn't warn you that you are entering the teaching profession twenty years too late. "You simply have no idea what hellholes those classrooms are out there!" Our Southern city was under court order to integrate the following fall so I dismissed him as a "closet racist." However, I would remember his warning many times in the months to come.

Two weeks after midterm graduation, I began teaching seventh and eighth grade English classes euphemistically labeled "Basic English." Basically, this meant the students could not read above a third or fourth grade level and some could not write their own names. Their previous teacher had fled the city at midterm and I soon understood why, for they were totally out of control. They had physical, mental, and emotional disabilities I had never even heard about. I had no text, no materials, nor the vaguest notion of what to do with them. My principal was helpful: "Kathryn, don't try to teach these dummies anything - Just entertain them - Keep them as quiet as possible and out of the halls."

Unable to accept that, I looked up an old teacher in an inner-city high school who had taught such students for 20 years. Early in her career, her blunt, outspoken manner had offended the powers-that-be , who condemned her to a lifetime of teaching basic students. Ironically, she learned to love her punishment and she generously shared ideas, lesson plans, and materials.

She advised me to teach my students "survival skills," like using a telephone directory, reading a map, filling out application forms, reading want ads. Now my students had no particular interest in learning anything; they had already failed too many times. However, they loved to have me read good adventure stories to them and they loved movies, so I bribed them shamelessly; "Write three friendly letters on this pretty purple paper I brought you and then I'll read you a story. Find the five 'W's' in this news story and we'll see a movie."

I read them every suitable adventure story I could find and we looked at every movie in the media library, from Pecos Bill to the Kotex movie. Don't ask me if I taught them anything; I really don't know, but we survived in reasonably good condition and I hurried back to the university for a summer course on "Teaching Secondary Students to Read."

In comparison with that first year, my second year was a Sunday School picnic. Having passed my "initiation rites," I move up the hierarchical ladder to "normal" classes and let another green teacher take over the basic classes. I had just begun to think I might give Miss Florine Lasater a "run for her money," when the full impact of integration and a flourishing drug problem swept across our campus. We had bloody fights daily. Teachers were assaulted and young people merrily smoked marijuana and sniffed glue behind the gym. Our principal spent the days barricaded in his office. We despised him for being a coward, though we knew he was simply obeying orders to "take no action, try to keep the lid on, and above all, keep it out of the papers." He and many of his peers would take early retirement at the end of the year.

I'm not sure when I decided to quit teaching. It may have been when our chief drug pusher was thrown out of school one morning and reinstated that afternoon when his irate mother complained to the superintendent. More likely it was the last day of school during the "awards assembly." Because of rioting in he halls, we had to remain locked in our homerooms with those young people we had been able to corral. The principal would announce an honoree's name over the public address system; the student would then scurry to the office for his or her award and race back to the relative safety of a locked classroom.

"This isn't an educational system," I wailed to my husband, himself a principal. "It's a madhouse."

Two weeks after the term ended, I mailed in a sizzling resignation letter, gave away my beautiful lesson plans and bulletin boards, and went to work as executive secretary to our city's leading realtor. The pay was much better, there were no papers to grade, and my office was blessedly peaceful and quiet. I told everyone how much happier I was. Three years later, I returned to the classroom. Why? Because I am a teacher and teachers must teach.

I started over again with Basic English and a lower salary in a smaller, somewhat calmer district. Even so, many of the same problems confront classroom teachers everywhere.

We are asked to help restructure society when we have been trained only to teach. There is little agreement on what should be taught, or how, or even whom. Teachers must deal with emotional and social problems for which we are totally unprepared. I have taught the third generation of drug users. Alcohol, gangs, teenage pregnancy, and suicide are growing problems, along with the specter of AIDS. Many of my students have carried guns or other weapons. Most administrators and citizens do not want to discuss or even acknowledge these issues, much less deal with them. Teachers must confront them daily.

Overriding all this, for me , is the mental lethargy of my students. More and more young people in our television oriented society demand entertainment rather than education. They want to be spectators and not participants, and, if the task requites any mental discipline, forget it. You have to sneak up on them, capture their interest, and try to teach them before they know what you're doing. Forget about asking their parents to back you up; parents have too many other pressing personal problems. You are on your own. As for grading and discipline, any teacher who tries to handle those areas fairly and sensibly takes both her physical and her professional life in her hands. Has any era in history presented more of a challenge to teachers?

In 1984, I left the public school classroom again and moved into the university arena. For me, it was like coming home after a long, difficult journey. However, I find some of the same problems that public school teachers know well.

I love to teach returning students who have had some hard knocks in the real world and, usually, have a thirst to learn. But, among younger students just out of high school, I often see the same mental lethargy that caused me to despair as a high school teacher. In a student survey this semester, 30% of my students could not tell me the name of a favorite book, having never read one for pleasure. Pop tests and classroom discussions reveal these same students will not (cannot?) read an assignment. Two of my students asked to do research papers on esoteric topics like "The Legalism of Marijuana" and "The History of Drag Racing" but could find little information in our library. When I suggested they research other subjects, their answers were identical: "I ain't interested in nothing else."

Tom Brokaw's recent report on the "Lost Generation" said today's young people can see no direct connection between study, mental discipline, and success. They view the college diploma as a magic paper, bestowed upon them for serving time in a classroom, a ticket to admit them to the world of fast cars and high living. While the prescription for dealing with these lost young people is unclear, one thing seems certain: in a time of traumatic social change, teachers and professors will continue to "take the rap" for many of society's failures.

I am still haunted by Miss Florine Lasater, Mr. Amos Ward, and Mark Hopkins, but they no longer intimidate me. I understand now that Miss Florine and Mr. Amos knew exactly who they were and what they had to teach. They were middle-aged, middle-class teachers, charged with teaching our community's children to read, write, and do arithmetic. If someone had told them not to impose middle class morality or an "outmoded" Protestant work ethic on their students, they would have rapped his knuckles with a ruler. As for Mark Hopkins, that other peerless pedagogue, I have this to say: you let me have a quiet log and a student thirsty to learn and you can keep our modern buildings, your air conditioning, your media centers, and your higher salaries - I'd teach for the sheer joy of it!

First Published by the Univeristy of Oklahoma in Creating The Quality School

This document was last modified on: